Thunderball (novel)

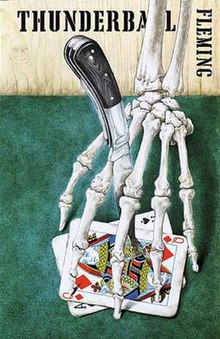

First edition cover, published by Jonathan Cape | |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 27 March 1961 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 253 |

| Preceded by | For Your Eyes Only |

| Followed by | The Spy Who Loved Me |

Thunderball is the ninth book in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, and the eighth Bond novel. It was published in the UK by Jonathan Cape on 27 March 1961. The first novelisation of an unfilmed James Bond screenplay, it was born from a collaboration by five people: Ian Fleming, Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo, although the shared credit of Fleming, McClory and Whittingham was the result of a courtroom decision.

The story centres on the theft of a pair of nuclear weapons by the crime organisation SPECTRE and the subsequent attempted blackmail of the Western powers for their return. James Bond of the Secret Service travels to the Bahamas to work with his friend Felix Leiter, who had been seconded back into the CIA for the investigation. Thunderball introduces SPECTRE's leader Ernst Stavro Blofeld, in the first of three appearances in Bond novels, with On Her Majesty's Secret Service and You Only Live Twice; the three novels are now known as the "Blofeld trilogy".

Thunderball has been adapted four times, once in a comic strip format for the Daily Express newspaper, twice for the cinema and once for the radio. The Daily Express strip was cut short on the order of its owner, Lord Beaverbrook, after Ian Fleming signed an agreement with The Sunday Times to publish a short story. On screen, Thunderball was released in 1965 as the fourth film in the Eon Productions series, with Sean Connery as James Bond. The second adaptation, Never Say Never Again, was released as an independent production in 1983 also starring Connery as Bond; it was produced by McClory. BBC Radio 4 aired an adaptation in December 2016, in which Toby Stephens played Bond.

Plot

[edit]During a meeting with his superior, M, the Secret Service agent James Bond learns that his latest physical assessment is poor because of excessive drinking and smoking. M sends Bond to a health clinic for a two-week treatment to improve his condition. At the clinic Bond encounters Count Lippe, a member of the Red Lightning Tong criminal organisation from Macau. When Bond learns of the Tong connection, Lippe tries to kill him by tampering with a spinal traction table on which Bond is being treated. Bond is saved by a nurse and later retaliates by trapping Lippe in a steam bath, causing second-degree burns and sending him to hospital for a week.

The Prime Minister receives a communiqué from SPECTRE (the Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion), a private criminal enterprise under the command of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. SPECTRE has hijacked a Villiers Vindicator and seized its two nuclear bombs, which it will use to destroy two major targets in the Western hemisphere unless a ransom is paid. Lippe was dispatched to the clinic to oversee Giuseppe Petacchi, an Italian Air Force pilot stationed at a nearby bomber squadron base, and post the communiqué once the bombs were in SPECTRE's possession. Although Lippe has accomplished his tasks, they were delayed; Blofeld considers him unreliable because of his clash with Bond and has him killed.

Acting as a NATO observer of Royal Air Force procedure, Petacchi is in SPECTRE's pay to hijack the bomber in mid-flight by killing its crew and flying it to the Bahamas, where he ditches it in the ocean and it sinks in shallow water. SPECTRE kills Petacchi, camouflages the wreck and transfers the nuclear bombs onto the cruiser yacht Disco Volante for transport to an underwater hiding place. Emilio Largo, second-in-command of SPECTRE, oversees the operations.

The Americans and the British launch Operation Thunderball to foil SPECTRE and recover the two atomic bombs. On a hunch, M assigns Bond to the Bahamas to investigate. There, Bond meets his friend Felix Leiter, who has been recalled to duty by the CIA from the Pinkerton detective agency because of the Thunderball crisis. While in Nassau, Bond meets Dominetta "Domino" Vitali, Largo's mistress and Petacchi's sister. She is living on board the Disco Volante and believes Largo is on a treasure hunt, although Largo makes her stay ashore while he and his partners supposedly survey the ocean for treasure. After seducing her, Bond informs her that Largo arranged her brother's death and recruits her to spy on Largo. Domino re-boards the Disco Volante with a Geiger counter disguised as a camera, to ascertain if the yacht has been used to transport the bombs. She is discovered and Largo tortures her for information.

Bond and Leiter alert the Thunderball war room of their suspicions of Largo and join the crew of the American nuclear submarine Manta as the ransom deadline nears. The Manta chases the Disco Volante to capture it and recover the bombs en route to the first target. Bond and Leiter lead a dive team in a fight against Largo's crew and a battle ensues. Bond stops Largo from escaping with the bombs; Largo corners him in an underwater cave and is about to kill him, only to be killed by Domino with a shot from a spear gun. The fight leaves six American divers and ten SPECTRE men dead, including Largo, and the bombs are recovered safely. As Bond recuperates in hospital, Leiter explains that Domino told Largo nothing under torture and later escaped from the Disco Volante to get revenge on him. Learning that she is also recovering from injuries, Bond crawls into her room and falls asleep at her bedside.

Background and writing history

[edit]The author Ian Fleming had long considered the possibility of his literary creation James Bond appearing on screen, and he had been in discussion with the filmmaker Sir Alexander Korda about a version of the 1954 novel Live and Let Die, although this came to nothing.[1][2] In 1954 the American CBS television network paid Fleming $1,000 for the rights to turn his first novel, Casino Royale, into a one-hour television adventure as part of the dramatic anthology series Climax Mystery Theater.[3][a][b] In June 1956 the author began a collaboration with the television producer Henry Morgenthau III on a planned television series, Commander Jamaica, which was to feature the Caribbean-based character James Gunn. The project foundered and Fleming used the plot as the basis for his 1958 novel Dr. No.[6][7]

In mid-1958 Fleming and his friend Ivar Bryce began talking about the possibility of producing a film with Bond as the protagonist.[8] At that time Fleming had published seven Bond novels in the preceding seven years.[c] Bryce introduced Fleming to the writer and director Kevin McClory, who was making the film The Boy and the Bridge at the time.[8][10] Bryce was part-financing the film, which was being produced through a partnership between Bryce and McClory under the name Xanadu Productions; the company was named after Bryce's Bahamian home.[11] Fleming suggested that Live and Let Die (1954) or From Russia, with Love (1957) would be the best options.[12]

In May 1959 Fleming, Bryce, Cuneo and McClory met first at Bryce's Essex house and then in McClory's London home as they came up with a story outline which was based on an aeroplane full of celebrities and a female lead called Fatima Blush.[13][14] McClory was fascinated by the underwater world and wanted to make a film that included it.[8] Over the next few months, as the story changed, there were ten outlines, treatments and scripts.[13] Much of the attraction Fleming felt working alongside McClory was based The Boy and the Bridge,[15] which was the official British entry to the 1959 Venice Film Festival.[10] When the film was released in July 1959, it was poorly received, and did not do well at the box office;[16] Bryce and Fleming became disenchanted with McClory's ability as a result.[17] In October 1959, with Fleming spending less time on the film project,[16] McClory introduced the experienced screenwriter Jack Whittingham to the writing process.[18]

In November 1959 Fleming left to travel around the world on behalf of The Sunday Times, material for which Fleming also used for his non-fiction travel book, Thrilling Cities.[19] On his travels—through Japan, Hong Kong and into the US—Fleming met with McClory and Ivar Bryce in New York; McClory told Fleming that Whittingham had completed a full outline which, he said, was ready to shoot.[20] Back in Britain in December 1959, Fleming met with McClory and Whittingham for a script conference and shortly afterwards McClory and Whittingham sent Fleming a script, Longitude 78 West, which Fleming considered to be good, although he changed the title to Thunderball.[21]

Fleming travelled to his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica in January 1960; that month McClory visited him. Fleming explained his intention of delivering the screenplay to MCA, with a recommendation from him and Bryce that McClory act as producer.[22][23] Fleming also told McClory that if MCA rejected the film because of McClory's involvement, then McClory should either sell his services to MCA, back out of the deal, or open an action in the courts.[22][24]

Writing

[edit]Before Fleming left for Jamaica, he wrote to his friend and copy editor William Plomer that he was "terribly stuck with James Bond. What was easy at 40 is very difficult at 50. I used to believe—sufficiently—in Bonds and blondes and bombs. Now the keys creak as I type and I fear the zest may have gone."[25] Once at Goldeneye, Fleming struggled to find fresh ideas for the plot of his novel and he based the novel on he screenplay written by himself, Whittingham, McClory and Cuneo.[26][23] Fleming had previously used his former scripts or treatments to form the basis of a novel, as he had done with the 1958 novel Dr. No and 1960 short stories "For Your Eyes Only", "From a View to a Kill" and "Risico".[27][28]

Fleming followed his usual practice, which he later outlined in Books and Bookmen magazine: "I write for about three hours in the morning ... and I do another hour's work between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written ... By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day."[29] On his return from Jamaica he wrote to Plomer with a copy of the manuscript:

You may say that it needs drastic re-writing. I certainly got thoroughly bored with it after a bit, and I have not even been able to re-read it, though I have just begun correcting the first chapters. They are not too bad—it is the last twenty chapters that glaze my eyes.[30][31]

In addition to Longitude 78 West, other titles proposed for the novel included SPECTRE and James Bond of the Secret Service.[16][27] The title Thunderball came from a conversation Fleming had about a US atomic test.[32] Although Fleming did not date the events within his novels, John Griswold and Henry Chancellor—both of whom wrote books for Ian Fleming Publications—have identified timelines based on episodes and situations within the novel series as a whole. Chancellor put the events of Thunderball in 1959; Griswold is more precise and considers the story to have taken place between May to early June 1959.[33][34]

Plagiarism accusation and court case

[edit]In March 1961 McClory read an advance copy of the book; within ten days he had decided to start legal proceedings for breach of copyright. He and Whittingham petitioned the High Court in London for an injunction to stop publication and the case was heard on 24 March. The judge, Mr Justice Wilberforce, allowed the book to be published as publication date was so close and 32,000 copies were already with booksellers, although the door was left open for McClory to pursue further action at a later date.[35][36] Two weeks after the case Fleming had a heart attack during a regular weekly meeting at his employers, The Sunday Times.[37]

On 19 November 1963 the case of McClory and Whittingham v Fleming, Jonathan Cape Ltd and Bryce was heard at the Chancery Division of the High Court; it lasted three weeks. Fleming's health had been poor for a while and he suffered two heart attacks while the case was running.[38][39] Under advice from Bryce, Fleming settled out of court. McClory gained the literary and film rights for the screenplay, while Fleming was given the rights to the novel, although it had to be recognised as being "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the Author".[40] On settlement, Fleming admitted "'that the novel reproduces a substantial part of the copyright material in the film scripts'; 'that the novel makes use of a substantial number of the incidents and material in the film scripts'; and 'that there is a general similarity of the story of the novel and the story as set out in the said film scripts'".[41] On 12 August 1964, nine months after the trial ended, Fleming suffered another heart attack and died aged 56.[42][43]

Script elements

[edit]When the script was first drafted in May 1959 with the storyline of an aeroplane of celebrities in the Atlantic, it included elements from Fleming's friend Ernie Cuneo, who included ships with underwater trapdoors in their hulls and an underwater battle scene.[44] The Russians were originally the villains,[13] then the Sicilian Mafia, but this was later changed again to the internationally operating criminal organisation, SPECTRE. Both McClory and Fleming claim to have come up with the concept of SPECTRE; Fleming's biographer Andrew Lycett and Robert Sellers, who wrote a history of the Thunderball controversy, both consider Fleming as the originator of the group, Lycett saying that "[Fleming] proposed that Bond should confront not the Russians but SPECTRE",[44] while Sellers describes SPECTRE as Fleming's "most significant contribution to the entire Thunderball story-line".[45] Fleming described SPECTRE—short for Special Executive for Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion—as "an immensely powerful organisation armed by ex-members of Smersh, the Gestapo, the Mafia and the Black Tong of Peking" which was "placing these bombs in NATO bases with the objective of then blackmailing the Western powers for £100 million or else".[46]

Sellers notes that Fleming had used the word "spectre" previously: in the fourth novel, Diamonds Are Forever, for a town near Las Vegas called "Spectreville", and a cryptograph decoder in From Russia, with Love was called the "spektor".[46] Those elements which can be put down to McClory and Whittingham (either separately or together) include the airborne theft of a nuclear bomb,[47] "Jo" Petachi and his sister Sophie, and Jo's death at the hands of Sophie's boss. The remainder of the screenplay was a two-year collaboration among Fleming, Whittingham, McClory, Bryce and Cuneo.[48]

Development

[edit]Inspirations

[edit]As with the previous novels in the series, aspects of Thunderball come from Fleming's own experiences: the visit to the health clinic was inspired by his own 1955 trip to the Enton Hall health farm near Godalming,[49][d] and Bond's medical record, as read out to him by M, is a slightly modified version of Fleming's own.[51] The name of the health farm, Shrublands, was taken from that of a house owned by the parents of his wife's friend, Peter Quennell.[52] Fleming dedicates a quarter of the novel to the Shrublands setting and the naturalist cure Bond undergoes.[53]

Bond's examination of the hull of Disco Volante was inspired by the ill-fated mission undertaken on 19 April 1956 by "Buster" Crabb , the ex-Royal Navy frogman, on behalf of MI6. He examined the hull of the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze that had brought Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin on a diplomatic mission to Britain. Crabb disappeared in Portsmouth Harbour and was never seen again.[54] As well as having Crabb in mind, Fleming would also recall the information about the 10th Light Flotilla, an elite unit of Italian navy frogmen who used wrecked ships in Gibraltar to launch attacks on Allied shipping.[55] The specifications for Disco Volante had been obtained by Fleming from the Italian ship designer, Leopold Rodriguez.[32]

As often happened in Fleming's novels, several names were taken from those of people he had known. Blofeld's name comes from Tom Blofeld, a Norfolk farmer and a fellow member of Fleming's gentlemen's club Boodle's; Tom who was a contemporary of Fleming's at Eton.[56][e] When Largo rents his beachside villa, it is from "an Englishman named Bryce", whose name was taken from Ivar Bryce, while Largo's beachside villa was based on Bryce's Jamaican property Xanadu.[52]

Other names used by Fleming included a colleague at The Sunday Times, Robert Harling, whose name was used by the Commissioner of Police Harling, while an ex-colleague from his stock broking days, Hugo Pitman, became Chief of Immigration Pitman and Fleming's golfing friend, Bunny Roddick, became Deputy Governor Roddick.[58]

Characters

[edit]The central character in the novel is James Bond. According to Raymond Benson—the author of the continuation Bond novels—the Bond character is developed further from the previous novels, including a sharper sense of humour and an awareness of his sense of mortality.[59] The book begins with the details of his recent medical being examined. It is recorded that he smokes sixty high-nicotine cigarettes a day and an "average daily consumption of alcohol is in the region of half a bottle of spirits of between sixty and seventy proof".[60][61] One study, undertaken by doctors, estimates this intake to be equivalent to drinking 105 units of alcohol a week; as at 2025 the UK's medical recommendations for an adult male are for a maximum of 21 units per week.[62] The novel also gives a small insight into Bond's views on social matters, which are described by the media historian James Chapman as being "conservative in the extreme",[63][64] when Bond takes an instant dislike of a young taxi-driver he describes as "typical of the cheap self-assertiveness of young labour since the war".[65]

Bond was joined in his mission by his friend, the CIA agent Felix Leiter, who had his largest role to date in a Bond story.[66] Leiter's humour is the source of the verbal comedy in the book,[66][67] while the incapacity he suffered in Live and Let Die had not led to bitterness or to his being unable to join in with the underwater fight scene towards the end of the novel.[66][f]

Domino Vitali has many characteristics that Bond found admirable, including her sense of independence.[69] Fleming describes her as "an independent, a girl of authority and character. She might like the rich, gay life but, so far as Bond was concerned, that was the right kind of girl".[70] He goes on to describe her approach to sex: "She might sleep with men, obviously did, but it would be on her terms, not theirs",[71] and Chapman observes that the freedom to make her own sexual choices were possibly the early signs of the sexual liberation that made part of the counterculture of the 1960s.[72]

The cultural historians Janet Woollacott and Tony Bennett see masculine aspects to he character which manifest as "excessive aggressiveness and over-dominating bearing" which, they say, could be connected to her full first name, Dominetta, which translates to "little dominator".[73] Fleming stresses such a masculine attitude in her approach to driving:[73]

But this girl drove like a man. She was entirely focused on the road ahead and on what was going on in her driving mirror, an accessory rarely used by women except for making up their faces. And, equally rare in a woman, she took a man's pleasure in the feel of her machine[74]

Domino is one of several women to come to Bond's aid at crucial moments in the books, and saves Bond's life at the end by killing Largo.[75][g]

Emilio Largo is the head of the SPECTRE team involved in stealing the nuclear bombs, and despite being the main adversary for Bond, he is not the primary antagonist, which is Blofeld.[61] The Anglicist Robert Druce describes Largo as "a barely sketched-in 'playboy' character".[28] As with most villains in the Bond novels, there is an unattractive physical attribute and although good looking, Largo's hands "were almost twice the normal size, even for a man of his stature, ... they looked ... almost like large brown furry animals quite separate from their owner".[76][77] The cultural critic Umberto Eco describes Largo as handsome but "vulgar and cruel"; while noting that most of Fleming's villains were monstrous, Eco considers that Largo's "monstrosity is purely mental".[78] The cultural historian Sue Matheson observes that although Largo is a dangerous opponent, "he drinks crème de menthe frappes topped with maraschino cherries – a sweet and effete drink".[79]

Although Blofeld only appears in two chapters, Benson considers that it is he Bond battles, not Largo.[66] The literary analyst LeRoy L. Panek describes Blofeld as "not only enormously powerful and grotesque, but ... also part intellectual and part 'gentleman crook'."[80] Blofeld differs from other villains in the Bond series, according to the literary historian Lars Ole Sauerberg. The villains in Fleming's previous novels are either criminals with large ambitions or those who commit crimes in order to complete their larger plans, Blofeld occupies his own classification as the only one of whom it is not possible to distinguish between a criminal act as a means or an end.[h] Sauerberg considers that Blofeld's motives are "in his general nihilism and destructive urge".[81] The sociologist Anthony Synnott notes that not only are nearly all Bond's enemies foreign, they are "doubly foreign".[82] Blofeld's ancestry shows he is Polish and Greek and, during the Second World War, he had betrayed Poland by working with the Abwehr, the Nazi military-intelligence service.[83][i]

With Blofeld appearing in two subsequent novels, this book forms the opening of what is known as the "Blofeld trilogy".[85][86] The second in the trilogy, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, ends with Blofeld involved in the murder of Bond's wife and the final chapter, You Only Live Twice, ends with Blofeld's death at Bond's hands.[87]

Style

[edit]In 1962 Fleming wrote of his work, "while thrillers may not be Literature with a capital L, it is possible to write what I can best describe as 'thrillers designed to be read as literature'."[88] To achieve this he used well-known brand names and everyday details to produce a sense of realism,[88][89] which the writer Kingsley Amis called "the Fleming effect".[90][j] Amis describes it as "the imaginative use of information, whereby the pervading fantastic nature of Bond's world ... [is] bolted down to some sort of reality, or at least counter-balanced".[92] According to Amis, Thunderball provides good examples of the use of the technique, including the full and detailed biographies in the novel for Blofeld, Largo and Petacchi; SPECTRE's headquarters on the Boulevard Haussmann and the working's of Fraternité Internationale de la Résistance Contre I'Oppression, SPECTRE's cover organisation; the American nuclear submarine, the USS Manta; and the pirates' treasure ships of the South Bahamas.[90]

Within the text Benson identifies what he described as the "Fleming Sweep", the use of "hooks" at the end of chapters to heighten tension and pull the reader into the next.[93] In Thunderball the sweep works well to build the tension, as does the fact that Bond and Leiter are working to a time limit to find the bombs.[59] With the removal of the Russian threat from the novel, Panek considers that Thunderball is "the ultimate heist ... with a tiny bit of international garnish thrown in."[94]

The Shrublands section of the story are a revenge fantasy, according to the Anglicist Robert Druce. The remainder of the novel is, in Druce's view, "a pastiche of an adventure story" of the likes of Sapper's Bulldog Drummond or Leslie Charteris's Saint stories.[95]

Themes

[edit]At the time Fleming was writing Thunderball the Cold War seemed to be easing, with relations between East and West thawing.[96][97] Fleming decided to use a politically neutral enemy for Bond; he wrote "I could not see any point in going on digging at [the Russians], especially when the co-existence thing seemed to be bearing some fruit. So I closed down SMERSH and thought up SPECTRE instead."[98] The Anglicist Christoph Lindner identifies the use of the organisation as part of a second wave of Bond villains, the first wave having comprised SMERSH.[98] The introduction of SPECTRE and its use over several books gives a measure of continuity to the remaining stories in the series, according to the historian Jeremy Black.[99] Black argues that SPECTRE represents "evil unconstrained by ideology"[100] and it partly came about because the decline of the British Empire led to a lack of certainty in Fleming's mind.[100] This is reflected in Bond's using US equipment and personnel in the novel, such as the Geiger counter and nuclear submarine.[101] Although the thaw in relations was present during the writing of Thunderball, the cold war escalated again shortly afterwards, with the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the construction of the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis all occurring in an eighteen-month period from April 1961 to November 1962.[96]

SPECTRE was originally short for Special Executive for Terrorism, Revolution and Espionage, but Fleming changed the last two elements to revenge and extortion, ensuring the organisation was free from ideological constraints and allowing him to change his focus away from any threat from the Soviets.[44][102]

Release and reception

[edit]Publication history

[edit]Thunderball was published on 27 March 1961 in the UK as a hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape; it was 253 pages long and cost 15 shillings.[103] 50,000 copies were printed and Cape sent out 130 review copies to critics and others and 32,000 copies of the novel had been sent to 864 UK booksellers and 603 outside the UK.[35][8][104] Cape spent £2,000 on advance publicity.[35][k] While the first edition stated "By Ian Fleming" on the title page, the second edition—published in 1964—included writing credits for McClory and Whittingham.[106][l]

Fleming's regular cover artist Richard Chopping once again provided the cover art for the novel. On 20 July 1960 Fleming wrote to him to ask if he could undertake the art for the next book, agreeing on a fee of 200 guineas, and instructed: "The picture would consist of the skeleton of a man's hand with the fingers resting on the queen of hearts. Through the back of the hand a dagger is plunged into the table top."[108][m]

For the Jamaican market, a paper wraparound band was produced which read "The thriller set in the Bahamas!"[104] Thunderball was published in the US by Viking Press and sold better than any of the previous Bond books.[110] In May 1963 Pan Books published a paperback version of Thunderball in the UK that sold 808,000 copies before the end of the year, 617,000 in 1964 and 809,000 in 1965.[111] In 1965 a special edition was produced to tie in with the release of the film Thunderball with a promotional tie-in with Player's Navy Cut, based on a passage in the book where Domino discusses a story behind the sailor in the logo. The version included a letter to Bond written by Domino asking him to read the pages with the story.[112]

Since its initial publication the book has been re-issued in hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and, as at 2025, has never been out of print.[113][114] In 2023 Ian Fleming Publications—the company that administers all Fleming's literary works—had the Bond series edited as part of a sensitivity review to remove or reword some racial or ethnic descriptors. The rerelease of the series was for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, the first Bond novel. For Thunderball, one of the barmen had his ethnicity edited out.[115]

Critical reception

[edit]Thunderball was generally well received by the critics.[110] Two of the reviews referred to the negative publicity that surrounded Dr. No (1958)—in particular the article "Sex, Snobbery and Sadism" by Paul Johnson in the New Statesman. Writing in The Guardian, Francis Iles, who thought the novel was "a good, tough, straightforward thriller on perfectly conventional lines", was left "wondering what all the fuss is about", noting that "there is no more sadism nor sex than is expected of the author of this kind of thriller".[116] Peter Duval Smith, writing in Financial Times, also took the opportunity to defend Fleming's work against negative criticism and said about Johnson’s review: "one should not make a cult of Fleming's novels: a day-dream is a day-dream; but nor should one make the mistake of supposing he does not know what he is doing."[117] Duval Smith thought that Thunderball was "an exciting story ... skilfully told". Of Fleming's books, he considered it "the best written since Diamonds Are Forever, four books back. It has pace and humour and style. The violence is not so unrelenting as usual: an improvement, I think."[117] Julian Symons, the critic for The Times, wrote that Thunderball "relies for its kicks far less than did Dr. No or Goldfinger on sadism and a slightly condescending sophistication."[103] The upshot, in the critic's opinion, was that "the mixture—of good living, sex and violent action—is as before, but this is a highly polished performance, with an ingenious plot well documented and plenty of excitement."[118]

Writing in The Washington Post, Harold Kneeland noted that Thunderball was "Not top Fleming, but still well ahead of the pack",[119] while Charles Poore, writing in The New York Times considered the Bond novels to be "post-Dostoevskian ventures in crime and punishment". Thunderball he found to be "a mystery story, a thriller, a chiller and a pleasure to read."[120] Poore identified aspects of the author's technique to be part of the success, saying "the suspense and the surprises that animate the novel arise from the conceits with which Mr. Fleming decorates his tapestry of thieving and deceiving".[120]

Writing in The Times Literary Supplement, Philip John Stead thought that Fleming "continues uninhibitedly to deploy his story-telling talents within the limits of the Commander Bond formula",[121] while "the usual beatings-up, modern style, are ingeniously administered to lady and gentleman alike".[121] As to why the novels were so appealing, Stead considered that "Fleming's special magic lies in his power to impart sophistication to his mighty nonsense; his fantasies connect with up-to-date and lively knowledge of places and of the general sphere of crime and espionage."[121] Overall, in Stead's opinion, with Thunderball "the mixture, exotic as ever, generates an extravagant and exhilarating tale and Bond connoisseurs will be glad to have it."[121] Julian Symons at The Sunday Times considered Fleming to have "a sensational imagination, but informed by style, zest and—above all—knowledge".[122] Duval Smith also expressed concern for the central character, saying "I was glad to see him [Bond] in such good form. Earlier he seemed to be softening up. He was having bad hangovers on half-a-bottle of whisky a day, which I don't call a lot, unless he wasn't eating properly."[117]

Anthony Boucher—described by Fleming's biographer, John Pearson as "throughout an avid anti-Bond and an anti-Fleming man"[123]—wrote: "As usual, Ian Fleming has less story to tell in 90,000 words than Buchan managed in 40,000; but Thunderball is still an extravagant adventure".[110]

Adaptations

[edit]A comic strip adaptation was published daily in the Daily Express and syndicated worldwide, beginning on 11 November 1961. The owner of the Daily Express, Lord Beaverbrook, cancelled the strip on 10 February 1962 after Fleming signed an agreement with The Sunday Times for them to publish the short story "The Living Daylights" The story was finished off in two days of strips.[124][125] The Thunderball strip was reprinted in 2005 by Titan Books as part of the Dr. No anthology that also includes Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia, with Love.[126]

Thunderball was planned to be the first Fleming novel made by Eon Productions, although the controversy over the novel's origins persuaded Eon to choose Dr. No instead.[27][127] In 1965 Eon released Thunderball, starring Sean Connery; it was their fourth Bond film. As well as listing Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman as producers, McClory was also included in the production team. Broccoli and Saltzman made a deal with McClory to undertake a joint production of Thunderball, which stopped McClory from making any further film version of the novel for a period of ten years.[128] Kevin McClory produced Never Say Never Again—a version of the Thunderball story—in 1983, with Connery as Bond.[129] In the 1990s McClory announced plans to make another adaptation of the Thunderball story, Warhead 2000 AD, with Timothy Dalton or Liam Neeson in the lead role, but this was eventually dropped.[130]

In December 2016 Thunderball was dramatised as a 90-minute radio play on BBC Radio 4; Toby Stephens played Bond, Tom Conti played Largo and Alfred Molina played Blofeld.[131][132]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ $1,000 in 1954 equates to approximately $11,000 in 2023, according to calculations based on the United States Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[4]

- ^ The hour-long episode, which starred Barry Nelson as Bond and Peter Lorre as the villain Le Chiffre, aired on 21 October 1954 as a live production. Due to the restriction of a one-hour play, the adapted version lost many of the details found in the book, although it retained its violence, particularly in Act III.[5]

- ^ These were Casino Royale (1953), Live and Let Die (1954), Moonraker (1955), Diamonds Are Forever (1956), From Russia, with Love (1957) and Dr. No (1958).[9]

- ^ Fleming's wife, Ann, had been there and recommended it to him.[50]

- ^ Tom Blofeld's son is Henry, a sports journalist, who was a cricket commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio.[57]

- ^ Leiter lost part of an arm and a leg in the story.[68]

- ^ Other examples include Tiffany Case in Diamonds Are Forever and Tracy di Vicenzo in On Her Majesty's Secret Service.[75]

- ^ Sauerberg identifies Le Chiffre (Casino Royale) and Mr Big (Live and Let Die) as ambitious criminals, and Hugo Drax, Doctor No and Goldfinger as those for who crime is a method to achieve an ultimate goal; all five are connected with the Soviet Union.[81]

- ^ Other "doubly foreign" villains include Dr. No (Dr. No; German-Chinese), Donovan "Red" Grant (From Russia, with Love; German and Irish, fighting for the Soviets), Count Lippe (Thunderball; Portuguese and Chinese).[84]

- ^ The "Fleming effect" was a mechanism Fleming continued to use in future books; Rupert Hart-Davis, the publisher and editor who was a close friend of Fleming's brother Peter, later remarked that "when Ian Fleming mentions any particular food, clothing or cigarettes in his books, the makers reward him with presents in kind ... Ian's are the only modern thrillers with built-in commercials."[91]

- ^ £2,000 in 1961 is approximately £56,230 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[105]

- ^ The authors' details on the title page of the second edition read: "Based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and Ian Fleming".[107]

- ^ A guinea was originally a gold coin whose value was fixed at twenty-one shillings (£1.05). By this date the coin was obsolete and the term simply functioned as a label for that sum.[109] According to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, 200 guineas in 1961 is approximately £5,900 in 2023.[105]

References

[edit]- ^ Benson 1988, p. 8.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 250.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 264; Black 2005, p. 10; Bennett & Woollacott 2009, p. 14.

- ^ McCusker 1996a; McCusker 1996b; "Consumer Price Index, 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 2009, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 17.

- ^ "Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles". Ian Fleming Publications.

- ^ a b Lycett 1996, p. 348.

- ^ Sellers 2008, p. 16; Benson 1988, pp. 17–18; Lycett 1996, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Sellers 2008, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 18.

- ^ Pearson 1966, p. 371.

- ^ Pearson 1966, p. 367.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Pearson 1966, pp. 372–373.

- ^ Pearson 1966, p. 374.

- ^ Pearson 1966, p. 375.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 359.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 231.

- ^ a b Pearson 1966, p. 381.

- ^ a b Benson 1988, p. 20.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 22.

- ^ Sellers 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 364.

- ^ a b c Gilbert 2012, p. 297.

- ^ a b Druce 1992, p. 63.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 362; Benson 1988, p. 20; Fleming 2009, p. 320.

- ^ Fleming 2015, p. 241.

- ^ Druce 1992, p. 64.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2008, p. 199.

- ^ Griswold 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c "Law Report, March 24". The Times.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 21; Sellers 2008, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 384.

- ^ Sellers 2008, p. 113.

- ^ "Law Report, November 20". The Times.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 432.

- ^ McKeown 2001.

- ^ Lycett 1996, pp. 442–443.

- ^ Sellers 2007.

- ^ a b c Lycett 1996, p. 350.

- ^ Sellers 2008, p. 23.

- ^ a b Sellers 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 365.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 356.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 290.

- ^ Parker 2014, p. 208.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 164.

- ^ a b Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 145.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Macintyre 2008a, p. 36.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 366.

- ^ a b Benson 1988, p. 124.

- ^ Fleming 1961, p. 11.

- ^ a b Benson 1988, p. 125.

- ^ Johnson, Guha & Davies 2013, pp. 2, 3.

- ^ Chapman 2018, p. 208.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 112.

- ^ Fleming 1961, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 126.

- ^ Panek 1981, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 100.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 118.

- ^ Fleming 1961, p. 116.

- ^ Fleming 1961, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Chapman 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 119.

- ^ Fleming 1961, p. 117.

- ^ a b Chapman 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Fleming 1961, p. 102.

- ^ Sternberg 1983, p. 173.

- ^ Eco 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Matheson 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Panek 1981, p. 213.

- ^ a b Sauerberg 1984, p. 165.

- ^ Synnott 1990, pp. 413–414.

- ^ Fleming 1961, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Synnott 1990, p. 413.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 24.

- ^ a b Fleming 2009, p. 320.

- ^ Butler 1973, p. 241.

- ^ a b Amis 1966, p. 112.

- ^ Lyttelton & Hart-Davis 1979, p. 92.

- ^ Amis 1966, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 85.

- ^ Panek 1981, p. 205.

- ^ Druce 1992, p. 192.

- ^ a b Black 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Sauerberg 1984, p. 167.

- ^ a b Lindner 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 49.

- ^ a b Black 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Black 2005, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Parker 2014, p. 256.

- ^ a b "New Fiction". The Times.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2012, p. 304.

- ^ a b Clark 2023.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, p. 306.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Fleming 2015, p. 243.

- ^ Besly 1997, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, p. 363.

- ^ "Thunderball". WorldCat.

- ^ Simpson 2023.

- ^ Iles 1961, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Duval Smith 1961, p. 20.

- ^ Symons 1961, p. 27.

- ^ Kneeland 1961, p. E7.

- ^ a b Poore 1961.

- ^ a b c d Stead 1961, p. 206.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 165.

- ^ Pearson 1966, p. 99.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- ^ McLusky et al. 2009, p. 287.

- ^ Bignell 2018, p. 52.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 184.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Rye 2006.

- ^ "James Bond: Thunderball". BBC Genome.

- ^ "James Bond: Thunderball". BBC.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Amis, Kingsley (1966). The James Bond Dossier. London: Pan Books. OCLC 154139618.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: The Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. London: Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (1987). Bond and Beyond: The Political Career of a Popular Hero. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4160-1361-0.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-8528-3233-9.

- Besly, Edward (1997). Loose Change: A Guide to Common Coins and Medals. Cardiff: National Museum Wales. ISBN 978-0-7200-0444-1.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Butler, William Vivian (1973). The Durable Desperadoes. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-14217-2.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Chapman, James (2015). "'Women Were for Recreation': The Gender Politics of Ian Fleming's James Bond". In Funnell, Lisa (ed.). For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond. London New York: Wallflower Press. pp. 7–18. ISBN 978-0-2311-7615-6.

- Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- Druce, Robert (1992). This Day our Daily Fictions: An Enquiry into the Multi-Million Bestseller Status of Enid Blyton and Ian Fleming. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-9-0518-3401-7.

- Fleming, Fergus (2015). The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming's James Bond Letters. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-6328-6489-5.

- Fleming, Ian (1961). Thunderball. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 561010890.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-8528-6040-5.

- Fleming, Ian (2009). "Ian Fleming on Writing Thrillers". Devil May Care. By Faulks, Sebastian. London: Penguin Books. pp. 314–321. ISBN 978-0-1410-3545-1.

- Gilbert, Jon (2012). Ian Fleming: The Bibliography. London: Queen Anne Press. ISBN 978-0-9558-1897-4.

- Griswold, John (2006). Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming's Bond Stories. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-3100-1.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (2009). "The Moments of Bond". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Eco, Umberto (2009). "The Narrative Structure of Ian Fleming". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-8579-9783-5.

- Lyttelton, George; Hart-Davis, Rupert (1979). Lyttelton–Hart-Davis Letters. Vol. 2. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-3673-1.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Hern, Anthony; Fleming, Ian (2009). The James Bond Omnibus Vol.1. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-364-3.

- Panek, LeRoy (1981). The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890–1980. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-8797-2178-7.

- Parker, Matthew (2014). Goldeneye. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-0919-5410-9.

- Pearson, John (1966). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 441370610.

- Sauerberg, Lars Ole (1984). Secret Agents in Fiction: Ian Fleming, John le Carré and Len Deighton. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3127-0846-7.

- Sellers, Robert (2008). The Battle for Bond. Sheffield, South Yorkshire: Tomahawk Press. ISBN 978-0-9557-6700-5.

- Strong, Jeremy, ed. (2018). James Bond Uncovered. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76123-7. ISBN 978-3-3197-6122-0.

- Bignell, Jonathan. "James Bond's Forgotten Beginnings: Television Adaptations". In Strong (2018), pp. 61–86.

- Chapman, James. "James Bond and the End of Empire". In Strong (2018), pp. 203–222.

Inflation calculations

[edit]- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, John J. (January 1996a). "How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. 106 (2): 327–334.

- 1700–1799: McCusker, John J. (October 1996b). "How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States" (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 106 (2): 327–334.

- 1800–present: "Consumer Price Index, 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

Journals and magazines

[edit]- Johnson, Graham; Guha, Indra Neil; Davies, Patrick (12 December 2013). "Were James Bond's Drinks Shaken Because of Alcohol Induced Tremor?". British Medical Journal. 347 (f7255): f7255. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7255. PMC 3898163. PMID 24336307.

- Matheson, Sue (2004). "Primitive Masculinity / "Sophisticated" Stomach: Gender, Appetite, and Power in the Novels of Ian Fleming". CEA Critic. 67 (1): 15–24. JSTOR 44377581.

- Synnott, Anthony (1990). "The Beauty Mystique: Ethics and Aesthetics in the Bond Genre". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 3 (3): 407–426. doi:10.1007/BF01384969. JSTOR 20006960.

- Sternberg, Meir (1983). "Knight Meets Dragon in the James Bond Saga: Realism and Reality-Models". Style. 17 (2): 142–180. JSTOR 42945465.

Legal reports

[edit]- "Law Report, March 24". The Times. 25 March 1961. p. 12.

- "Law Report, November 20". The Times. 21 November 1963. p. 20.

- McKeown, M. Margaret (27 August 2001). "Danjaq et al. v. Sony Corporation et al" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

News

[edit]- Duval Smith, Peter (30 March 1961). "No Ethical Frame". Financial Times. p. 20.

- Iles, Francis (7 April 1961). "Criminal Records". The Guardian. p. 7.

- Kneeland, Harold (11 June 1961). "MI-5's James Bond and Other Sleuths". The Washington Post. p. E7.

- Macintyre, Ben (5 April 2008a). "Bond – the Real Bond". The Times. p. 36.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 30 March 1961. p. 15.

- Poore, Charles (4 July 1961). "Books of the Times". The New York Times. p. 17.

- Rye, Graham (7 December 2006). "Kevin McClory". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Sellers, Robert (30 December 2007). "'James Bond Would have Shot the Judge'". The Sunday Times. p. 10.

- Simpson, Craig (25 February 2023). "James Bond Books Edited to Remove Racist References". The Sunday Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023.

- Stead, Philip John (31 March 1961). "Mighty Nonsense". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 206.

- Symons, Julian (26 March 1961). "Enough to Make Sapper Turn Over...". The Sunday Times. p. 27.

Websites

[edit]- "Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles". Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- "James Bond: Thunderball". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- "James Bond: Thunderball". BBC Genome. 10 December 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2025. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

- "Thunderball". WorldCat. Retrieved 25 January 2025.